Is this a Bongo?

What is in a name?

The importance of inspirational teachers, voluntary play the correct terminology in the arts.

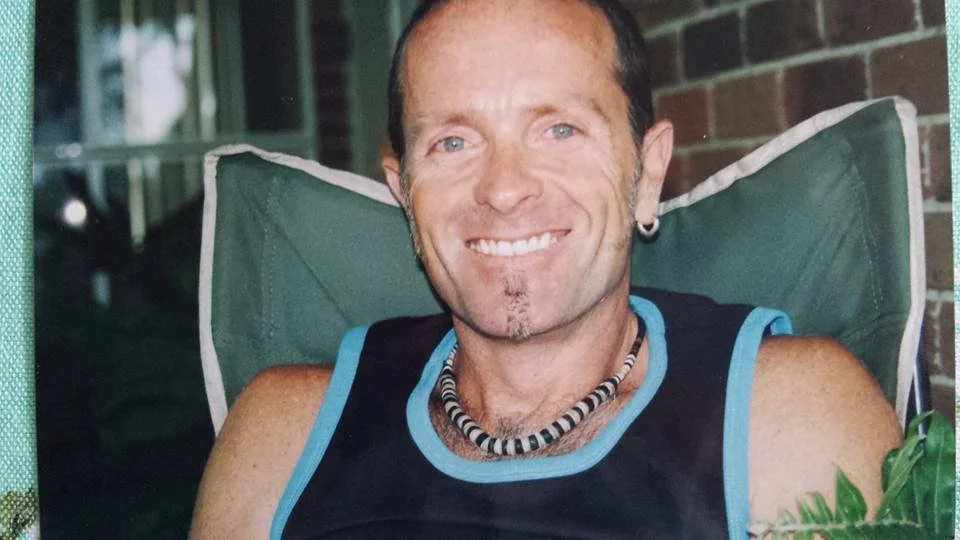

In 2004, After 5 or 6 years under the mentorship of two inspirational teachers, I began running weekly Samba classes at the age of 23. Motivated by the desire to work full time in the creative arts, I decided to study and lead a group of my own, as well as work more broadly in other groups. I wanted to try a different concept from anything else that existed in Western Australia at that time, although there may have been groups using the name of “Samba” in their title, I wanted to create a group that really sounded like a Brazilian drum section. My first teacher, Paul Barrett, was a flamboyant character who led a local community drumming group called “Freo Samba”, in which I did my first performances, largely unaware of the concept of “traditional” music. My second teacher, Alastair Van Schoor, inspired in me the belief that we could be a little more ambitious to sound authentic, regardless of our remoteness from the source of music we were playing. Unfortunately, neither of them are with us today but their contribution to my life and the local arts scene is incalculable.

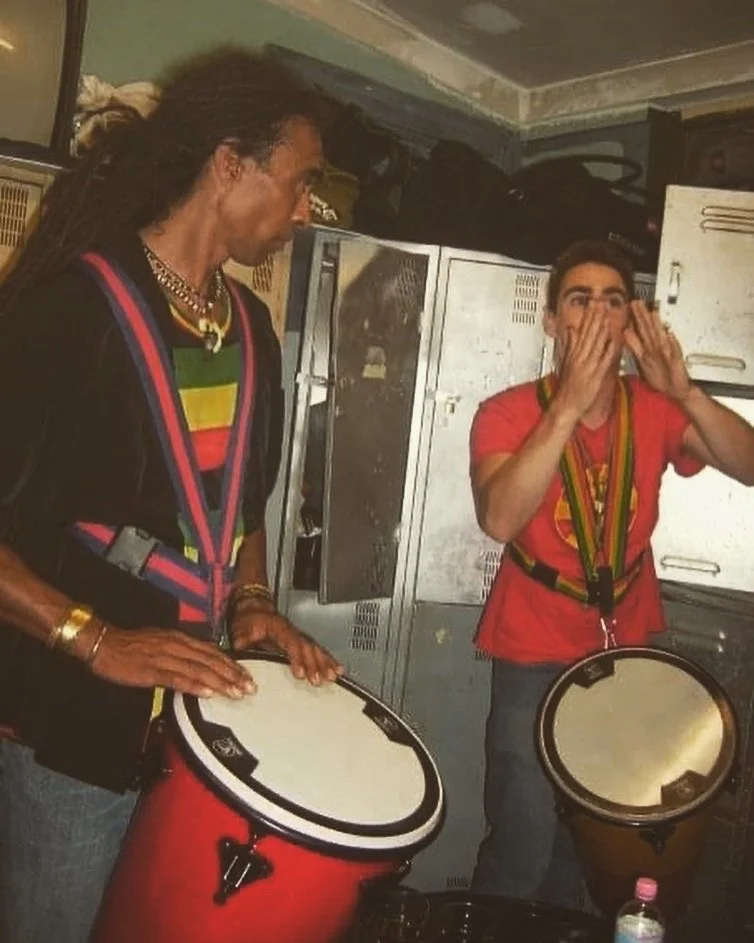

I first met Paul in 1998 and we worked closely for a short time. Despite it not being long, I was young so it was a very formative period for me. My first performances were in Freo Samba and my first paid gigs were in his smaller professional ensemble called “Curry Boyz”. We became close enough that Paul and I even lived together for 6 months or so. He was my introduction in to the rich arts scene of Fremantle as I came fresh out of high school. Some very memorable acts performing locally at the time were John Butler, Wunjo, LC Salsa, Rhibosome and Whak.

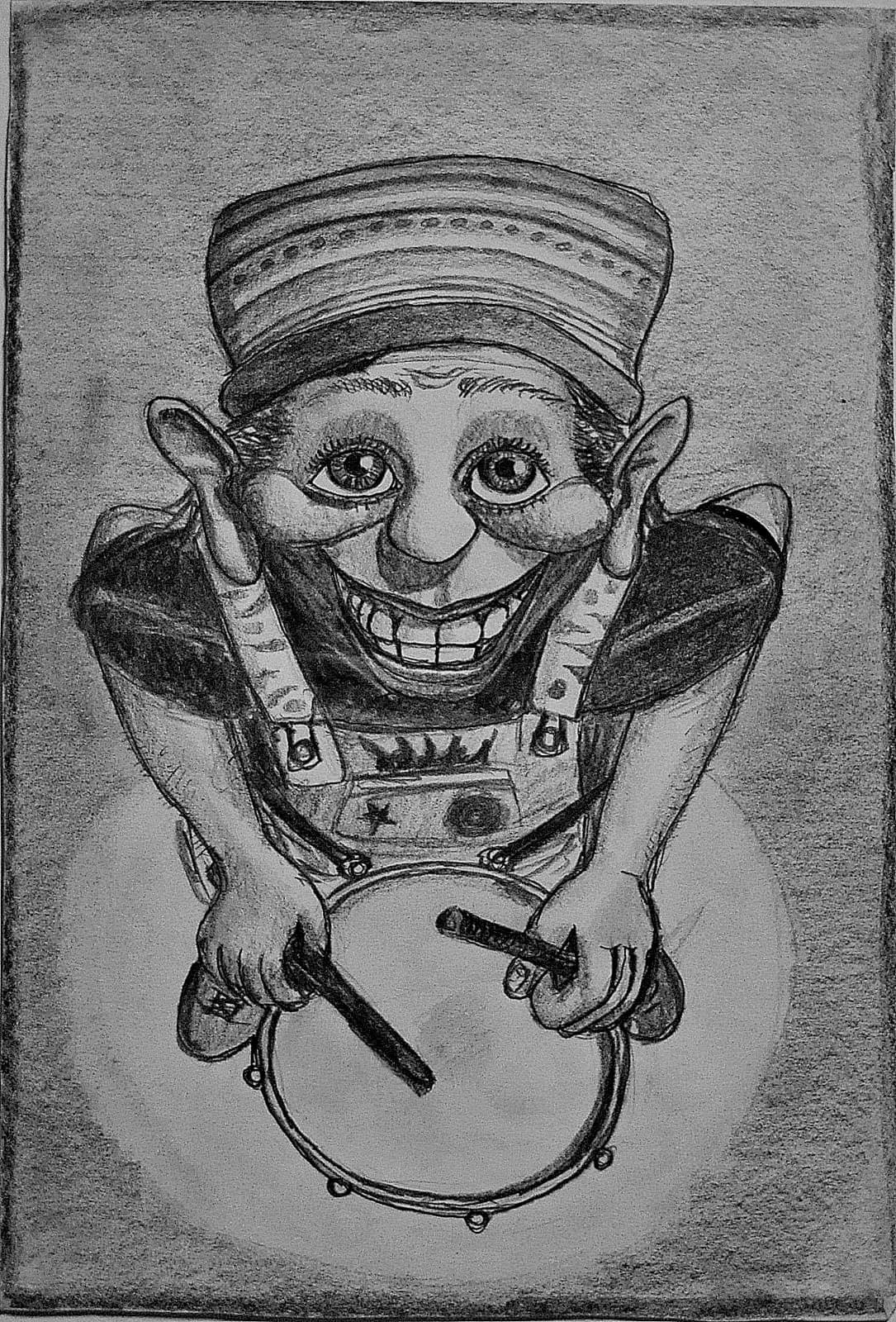

I’ll never forget the early days in Freo Samba as a special time, slathering myself in red paint, strapping on my drum and losing myself in an absolutely unbridled performance. It was especially wild and free before the year 1999, after that, Paul began introducing colour co-ordinated sections to his costuming, turning it into an extremely tight and impressive community street show. I guess like any artist, he aspired to do bigger and better things all the time and there was only so much he could do if the group was quite chaotic like it was when I first joined. He was a talented musician but he really excelled with the visual aspect of his shows.

Paul was very imaginative and he clearly drew many ideas from traditional arts from Africa and Brazil but he did not endeavour to sound or look authentic in that way, apart from being true to in his own originality. I think he really preferred the creative license of not having to delve too deeply into the cultures that he borrowed from. Apart from some loosely associated drum patterns to traditional Samba rhythms, his musical pieces and costuming was largely of his own invention. In his own words, Paul was a larrikin and there was a genius to his creativity that I look back on fondly.

So powerful was his concept that the legacy lives on, with the group having changed it’s name to WASAMBA in 2003 under new leadership but still largely basing it’s style in Paul’s ideas to this day. He had a massive impact on me and everything I’ve done since then as well and despite my critique about the lack of actual Samba rhythms in his group, I think there was something about it all that he got absolutely right.

My time with Paul was life changing but it was the artistic depth I found with Alastair Van Schoor and our long lasting friendship that shaped my career more than anyone else.

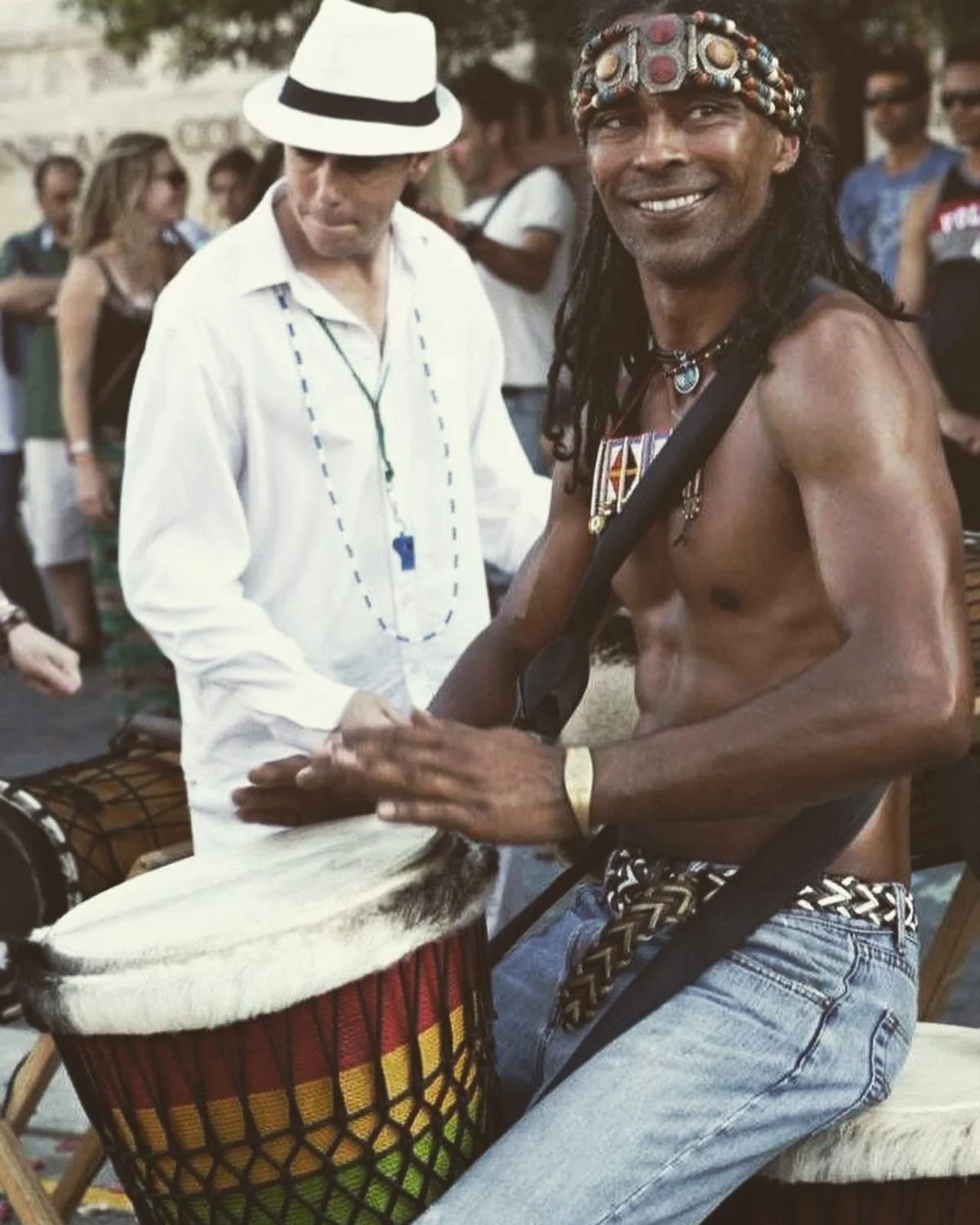

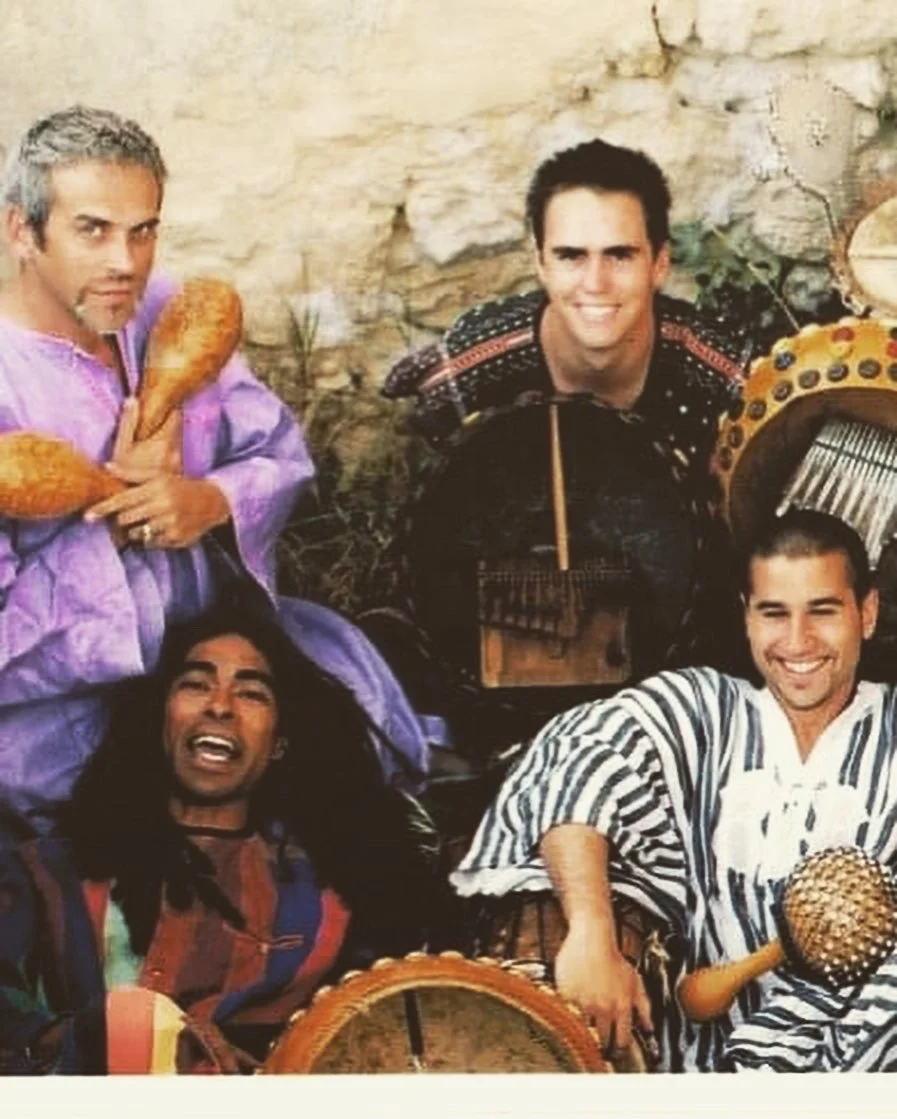

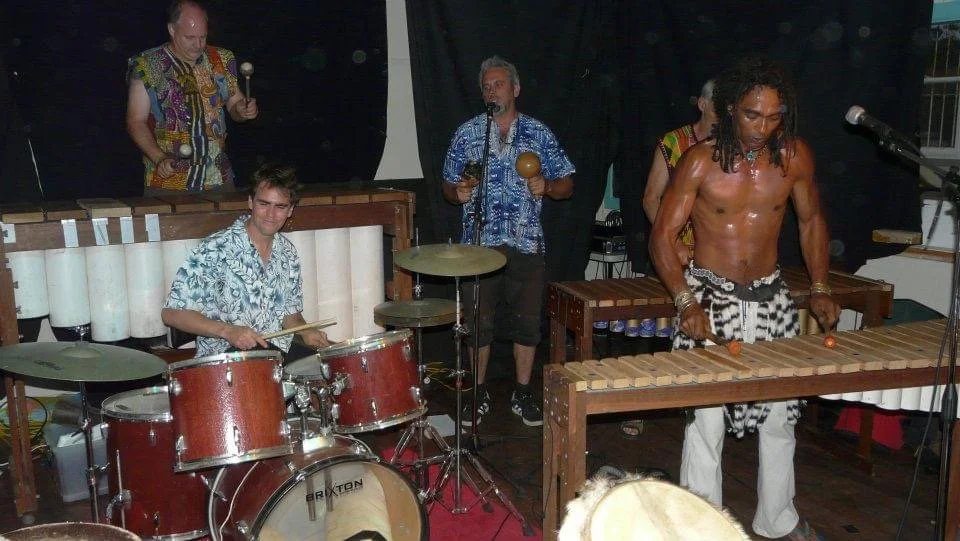

I met Alastair around the year 2000 and began playing in his percussion band, Deredjeff Dubar shortly after. Alastair profoundly influenced how I began to play music by showing me what it is to be really precise. He taught me to be more cognisant what I was playing, how to pitch a note with my voice and learn particular patterns that fit together in a musical dialogue.

It was Alastair that taught me that it is good to pay your respects to the ancestors and musical traditions by using the correct terminology that surrounds the music you play.

As with many percussionists in Australia will know, there is a common misconception here that any hand drum is a called a Bongo. Even myself, at the age of 15 had asked my mother to buy me a Bongo for Christmas, although I was unaware that what I wanted was in fact, a Djembe. So these days, usually the first thing I do in any class I deliver to a new group of people, is tell them the name of the instrument they are playing.

To me, it makes sense that this is like a common courtesy. Much like asking first before touching someone else’s belongings, it’s good to know something about the instrument you are playing.

I think Alastair was on a mission to not only share his love of music but also of the beauty of diversity, part of this, was emphasising the importance of respect, learning languages and correct terminology.

Between the years 2000 and 2005, I worked a lot with Alastair. We travelled around the state delivering classes to regional communities, as well as around the city. All the while, we worked on music for his bands, playing all manner of percussion instruments from Cuba, Zimbabwe, West Africa and more.

Alastair’s patience as a teacher, helped me believe that I had the potential to learn anything I wanted, if I put the time and dedication in to it.

With Alastair’s approach to music, I really loved how the traditional music had depth, that rhythms have significance to them, just as the terminology used to describe them. As I often say during my classes now, learning traditional music is like learning a new language, there is a vocabulary and phrasing that you can constantly expand upon. These foundations are all about dialogue. A conversation that can be built upon in multiple dimensions.

Another thing I learnt with Alastair was about how, as counterintuitive as it might be, limitations set you free. That by defining something, you can give it a place and differentiate it from other things. And that having these constraints actually facilitate creativity and development. So learning the defining features of a rhythm or the structure of a melodic scale is like learning new words. It introduces fresh ways to express yourself and see the world with a new perspective.

Alastair and I could sit and jam for hours and hours, exploring various musical themes and enthusiastically discussing our discoveries as we went along. I still feel the immense loss of my good friend. We continued playing together almost continuously for a couple of decades in various formats and he passed away less than two years ago.

Early on in our friendship, with my new found love of tradition, I began seeking out what defines musical genres with an almost “scientific” method. It became important for me to do as much research as possible, to learn about the origins, the terminology and the culture that surround the music I play. Alastair gave me that framework and opened the world of language and culture to me. An approach to study and practice that I had in mind when I started my own business, teaching and performing with my drumming school.

Being South African, Alastair was also strongly against racial divisions and believed music and culture belonged to humanity, regardless of a person’s origins or race. So I never stopped to question whether being mainly of English descent should be an impediment to my ambitions with Brazilian or African music.

In my education about Samba, I’ve managed to learn a substantial amount of Brazilian Portuguese and over the years I’ve become increasingly interested in learning languages in general, picking up little bits of many different languages, a lot of which, originate from Africa.

In my opinion, no matter how small the effort to learn new words from another language, every little bit is good for you. Learning how to say hello to someone in their language will often light up a person’s face with joy just at hearing the words come from your mouth. Language is truly at the base of all cultures around the world and though we may never fully understand them, every word we learn expands our mind in a healthy way.

It was a priceless to see the joy on the faces of people in Africa recently when I spoke their language. The value of our own language is often invisible and taken for granted, so when someone else learns it, we suddenly pay attention and see it’s worth.

Of course I can understand why people might be hesitant about learning new words. Learning a language is a daunting task. Diversity is certainly also complexity to some degree. It's complicated, tiring and difficult to learn new things and flooding ourselves with too much new information is counterproductive. As a teacher, trying to get this balance right, is quite difficult. To know where the line is between being encouraging students to push themselves and not overwhelming them is a constant challenge.

This was the beauty of Freo Samba. Paul took simple rhythmic patterns that made drumming accessible to everyone. What was required of people was more manageable and served as the perfect escape into a kind of fantasy world, where one could enjoy playing with youthful exuberance. Paul Barrett was a master at keeping things simple and fun. His leadership was extremely popular and he impacted countless people’s lives for this reason.

Whereas Alastair Van Schoor was masterful for different reasons. He enjoyed challenging people a little more and therefore, helping them realise they were capable of so much more than they could imagine. He also wanted people to realise that languages and cultures foreign to our own, might offer us a chance to experience new perspectives, epiphanies and self realisations.

Underlying any particular tradition is the universality of “play”. It really is the key word when it comes to music. The question might be, what is more important? Approaching an instrument with a child like innocence and playfulness that is accessible to all? Or is it learning the traditional terminology, techniques and phrasing in order to play?

The answer will be different depending on the context. Each individual has their own zone of proximal development but one thing is for sure, there is always room for improvement.

Though my two first teachers had very contrasting creative approaches to music and performance, I try to integrate the two as much as possible. I think both are important.

While it’s true that too much complexity makes life difficult, there are some basic things that we could pay attention to. Learning the difference between a Djembe and a Bongo or between Samba and Salsa might be a good start.

There is a tendency for people to avoid what is unknown, to learn new words, or to face what is challenging. Perhaps as a result, they don’t get a sense of what their potential is. I think this initiative, ultimately has to come from people themselves, voluntarily. I endeavour to get better at inspiring others to partake in the spirit of play, as my teachers did for me.

In loving memory of Alastair Van Schoor and Paul Barrett.